I have never read an article on South Asian speculative fiction (there are many) that didn’t feel painfully incomplete to me, so I decided to write my own. South Asian literature is a large and often unwieldy mass, emerging from disparate influences, even if we discount the regional languages and talk about only the works in the English. Speculative stories pop up in the most unexpected places. There is no uniform tradition and reading list, so I will try to touch on everything a little. (Perhaps inevitably, I will leave out some works of which I remain unaware—there is always more to learn, and to read.)

To begin with, nonrealist narratives abound in a culture where the major religion is pantheistic with no finite canon of scriptures. Unlike the Greek, Norse, or any other pantheon that is no longer actively worshiped, not every new piece of writing featuring Hindu gods is fantasy, or intended to be so. The largest body of Hinduism-related works currently available are instructional, philosophical, myth-revisionist, and (increasingly) right-wing religious propaganda. Epics like Ramayana and Mahabharata are still actively read by thousands of people seeking words to live by, just like the Bible. Hinduism is one of the four major world religions, with more than 15% of the world’s population adhering to it. Many of them are faithful and like to write about their beliefs. It pains me to find Western readers regularly conflating such works with fantasy. To think of other people’s actual faith as speculative fiction is a fairly heinous act of racism. Don’t be that person. In this article, I will only discuss narratives that are clearly intended to be read as works of fiction.

(translated from the

Bengali) by Satyajit Ray

A genre is defined by its own tradition as well as publishing conventions—hence the confusion over how to classify authors like Margaret Atwood or Haruki Murakami, who don’t actively identify as fantasy writers—but the further you go into history, genres tend to be defined by their actual format, as well. “Science fiction” as a distinct, recognizable genre term only came together in the early twentieth century, “fantasy” a few decades afterwards. The novel did not become a recognizable format until the late eighteenth century, and short stories were still kind of vague until the mid-nineteenth-century periodical boom in England. Older works—epics and folk tales from various cultures, the plays of Shakespeare, even relatively newer works like Frankenstein or Alice in Wonderland—can only be read as precursors of ideas and tropes that are further explored in SFF as it came to be, but not works in the genre itself. The authors of those works were not working within the genre, and their works cannot be completely made to fit into the genre conventions as we know them.

Why is this quick-and-dirty history-and-genre-theory lecture relevant to a discussion of South Asian speculative fiction?

Because without it, it’s impossible to recognize which works from a primarily non-Western but also postcolonial culture were written clearly to be genre, or even fiction. South Asia had a significant culture of letters in several languages for centuries before British colonization, including not only religious works but also poetry, plays, nonfiction, and oral narratives. Those works are not novels or short stories, and the boundaries of religious-vs-secular and realism-vs-nonrealism in them are often blurred, because these binaries which we now take for granted are also developments from Western literary thought.

Earliest Works of South Asian SFF

Dakshinaranjan Mitra Majumdar

The earliest novels and short stories in South Asia started appearing in the mid-nineteenth century, usually from writers who had the privilege of an English education and could read literature in English, in a country that was still the British Indian Empire. The shorthand to refer to this region would be India, since it was still that, but many of these authors may have lived their lives entirely within the parts of it that are now Pakistan and Bangladesh.

These earliest writers were also divided in their vision and the languages they worked in—some chose to write in English, others to adapt those essentially English formats to their own regional vernaculars. Many wrote in both. The works written in regional languages are perhaps more innovative in their craft since their authors were linguistic pioneers as well, but they have aged less well, especially to international readerships. They were also more popular in their time, since more readers had access to them, and had more influence on how the genre progressed to later readers and writers.

Bengali, Urdu, and Tamil were among the earliest languages of genre fiction in British India, with the publishers based out of—respectively—Calcutta, Lucknow, and Madras. The earliest works were horror, crime, “sensation” and detective stories, tall tales in the folkloric style (both original and curated), not unlike the genre fiction that was being written in England during the same decades.

What to read from this period:

Muhammad Husain Jah,

translated from the Urdu

by Musharraf Ali Farooqi

- Dastan-e Amir Hamza (1855), tall-tale adventures in Urdu by Ghalib Lakhnavi, translated to English by Musharraf Ali Farooqi

- Tilism-e-Hoshruba (1883), an oral-folktale-style epic in Urdu by Muhammad Husain Jah, translated to English by Musharraf Ali Farooqi. The first volume of this translation is available on Tor.com.

- Chandrakanta (1888), an epic fantasy novel in Hindi by Devaki Nandan Khatri. This was turned into an extremely popular Hindi TV serial in the mid-1990s, one which established the fantastic imagination of my entire generation.

- “Niruddesher Kahini” (1896), perhaps the first South Asian science fiction story, in Bengali by the scientist Jagadish Chandra Bose

- “Sultana’s Dream” (1905), a feminist utopian short story in English by Begum Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain, who lived in current-day Bangladesh

- Horror short stories like “Konkaal,” “Monihara,” “Mastermoshay,” and “Khudhito Pashan” (c. 1891–1917) in Bengali by Rabindranath Tagore, often found translated within collections of his other prose works

- Thakuma’r Jhuli (1907), curated collection of Bengali folk and fairy tales styled after the Grimm Brothers’ work by Dakshinaranjan Mitra Majumdar

- Tuntuni’r Boi (1911), collection of original children’s fables and Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne, a horror novel in Bengali by Upendrakishore Ray Chowdhury, largely untranslated, although GGBB was made into an acclaimed film adaptation made by Satyajit Ray, his grandson

- Sandesh (1913–25; 1929–34; 1961–), iconic Bengali children’s and YA magazine in which nearly all speculative fiction authors in Bengali have been published for over a century, largely untranslated apart from individual authors’ works

The Post-Independence Period

Fiction magazine (Bengali),

May 1971

The British Indian Empire was partitioned and given independence in 1947. As a result, the two richest regional literary traditions—Bengali and Urdu—were split between countries created on ideologically hostile premises. (Sri Lanka became independent in 1948. Bangladesh was further separated from Pakistan in 1971.) The Urdu literary scene in Lucknow dwindled after Independence, since Urdu fell out of favor as a literary language in India; while the younger literary centers in Lahore and Karachi had very little connection with readers in India. Calcutta continued to dominate the Bengali literary scene, while Dhaka’s own literary scene has been growing since the 1970s. Once again, the two literary communities developed separately from each other.

The political and historical rupture of continuity also created an ideological disconnect. Books and authors from one country were no longer widely distributed or read in the other. This was especially true of India, which established itself as the socio-cultural monolith in South Asia post-Independence and did not consume cultural products from the other countries, even as these countries consumed cultural products from India. The earliest compiled histories of “Indian literature” ignored works from the other South Asian countries. Generations of Indian readers and scholars grew up with no contact with works from the other countries, or only in languages they did not understand.

by Humayun Ahmed

As science fiction became more distinctly recognizable as a genre in the West through the twentieth century, the language that most directly caught the influence was Bengali. The original center of Bengali SFF was Calcutta, and this tradition has remained. I am from Calcutta—I grew up reading SFF and horror in Bengali and was deeply entrenched in genre culture. Every prominent Bengali author has written speculative fiction in some parts of their career—stories that are widely read, loved, and often included in school syllabi—since the speculative imagination is inseparable from realism in the Bengali literary culture. Many Indian SFF writers, even now, come from Calcutta, though not all of us write in Bengali.

On the other hand, since most SFF writers and scholars from India tend to be Bengali, the works from the other languages—which we don’t read in the original—end up getting cited and translated less frequently. Works from this period are either hard science fiction or horror, as well as a lot of crime fiction, with less and less overlap as these genres became settled into their own distinct categories.

What to read from this period:

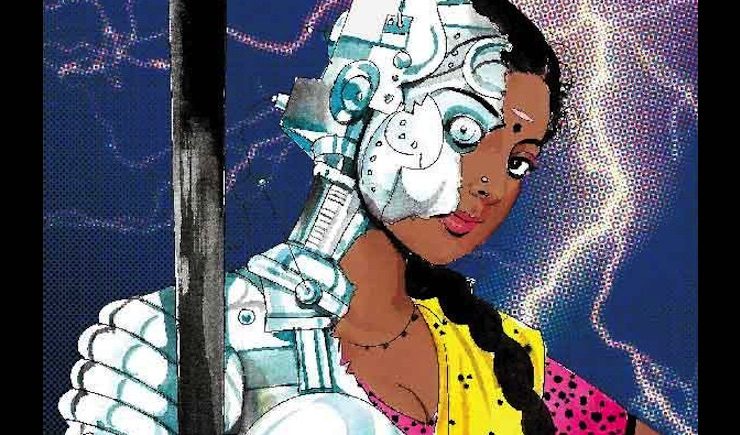

Tamil Pulp Fiction, Vol. 3

- The Professor Shonku series of science fiction novels and the Tarini Khuro series of paranormal novels in Bengali from Calcutta by Satyajit Ray, India’s most famous and prolific SFF writer who is known more commonly as a filmmaker in the West. Ray is the most widely translated author on this list, with many of his works available on Amazon.

- The Ghanada series of tall-tale/horror adventure novels in Bengali from Calcutta by Premendra Mitra, partially translated by Amlan Das Gupta

- Pulp SF magazines like Ashchorjo, Bismoy, and Fantastic in Bengali from Calcutta from the 1970s and ’80s, styled after Hugo Gernsback’s magazines and published by Ronen Roy and Adrish Bardhan, untranslated

- The Himu and Misir Ali series of paranormal novels in Bengali from Dhaka by Humayun Ahmed, largely untranslated

- Science fiction novels in Bengali from Dhaka by Muhammed Zafar Iqbal, largely untranslated

- Very popular children’s and young-adult fantasy novellas in Bengali from Calcutta by Leela Majumdar, Sunil Gangopadhyay, Shirshendu Mukhopadhyay; Urdu from Pakistan by A. Hameed, and many other writers—largely untranslated

- The Imran series of supernatural spy novels in Urdu from Lahore, originally by Ibn-e-Safi and later by Mazhar Kaleem. Some of Ibn-e-Safi’s novels have been translated and published by Blaft Publications in India.

- Kala Jadu, a horror/dark fantasy novel and other works in Urdu from Lahore by M.A. Rahat

- Devta, a serialized fantasy thriller novel in Urdu from Karachi by Mohiuddin Nawab, published in the magazine Suspense Digest for thirty-three years, making it longest continuously-published series on record

- Bleak, uncanny Kafkaesque short stories in Urdu from Lucknow by Naiyer Masud, partially translated

- Surreal stories like “The Wagon” in Urdu from Lahore by Khalidah Asghar, partially translated

- Science fiction novels in Sinhala from Colombo by Damitha Nipunajith, untranslated

- The Blaft Anthology of Tamil Pulp Fiction, Vols. 1, 2, 3, translated works of lurid genre fiction from authors in Tamil

Author’s Note: This section could not be compiled without the generosity of Vajra Chandrasekara, Usman T. Malik, and Dr. Abhijit Gupta.

Some further additions have been received with thanks from Tayyab, Sandeep Banerjee, Chelsea McGill, and Gautham Shenoy.

Part II of this article, featuring contemporary South Asian SFF writers writing in English, can be found here.

Mimi Mondal is a Dalit writer and the Poetry and Reprint Editor of Uncanny Magazine. Her first anthology, Luminescent Threads: Connections to Octavia Butler was published in 2017. Her short fiction has been published by PodCastle, Daily Science Fiction, Anathema, Juggernaut Books, and is forthcoming from Fireside and Tor.com. Mimi holds three masters’ degrees for no reason but pure joy. She was formerly a Junior Editor at Penguin Random House India; a Commonwealth Scholar in Publishing Studies at the University of Stirling, Scotland, UK; the Octavia Butler Scholar at Clarion West in 2015; and an Immigrant Artist Fellow at the New York Foundation for the Arts in 2017. She lives in New York, tweets from @Miminality, and always enjoys the company of monsters.

Interesting article! I hope Tor and the author decides to make a regular section of reviews/rec of fiction not written originally in English / other traditions.

It’s a pity that many are untranslated. When you say “untranslated”, does it means not translated in English or not translated in any other language? The Thakuma’r Jhuli collection sounds interesting.

Another question, could you explain a bit more about “very prominent Bengali author has written speculative fiction in some parts of their career—stories that are widely read, loved, and often included in school syllabi—since the speculative imagination is inseparable from realism in the Bengali literary culture“

I really appreciated the recommendations and the context accompanying them!

You missed a very important work of fiction. DEWTA by Mohiuddin Nawab. It was first into to both science fiction and fantasy for many of us

@1: Hello, thanks for the comment! I will try to address your points one by one.

Unfortunately, South Asian is the only tradition I am closely familiar with. I’d love to see recommendations from other non-Western SFF traditions as well, but I’m not the person who’s equipped to write them. Geoff Ryman writes an excellent series called 100 African Writers of SFF on Strange Horizons, if you’re interested.

For “untranslated” I mostly meant untranslated to English. Some of the works mentioned have probably been translated to other South Asian languages, but those editions are hard to track, especially for a person who doesn’t read all those languages, and also actually wrote this article from New York. There’s no easy-to-access archive, as far as I know.

Hm. To your third question. I grew up believing ghosts were a real thing, just like walls or streets and so on. What anyone (or any culture, as an overarching theme) considers “realism” is very strongly defined by what their understanding of reality is. In much of early realism in English, the Christian God doling out justice is real. “Fallen women” or queer people always coming to horrifically tragic ends is completely compatible with reality. Stories with such themes are canonized as realism.

I tried to approach the fact that the understanding of reality in many non-Western cultures has been fundamentally different from the West, more so in the past, as a result of which stories with ghosts, ancestors etc. have not always been considered a different genre of fiction. Nearly all Bengali authors of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries have written stories both with ghosts in them and without, and they’re all considered part of their general body of work. And there are a lot of Bengali authors – the language has an extremely rich and prolific literary tradition – so I mentioned only a few seminal works.

@2: I really appreciate your taking the time to comment, Kate! Con or Bust (and you) have been a lifesaver for me more than once. :)

@3: Duly noted, and thank you! I will include it in further discussions of South Asian SFF. :)

My Urdu references are unfortunately all from secondary sources, because I understand spoken Urdu but don’t read the Nastaliq script. Anything that I didn’t find mentioned in English on the Internet (or literary journals, but very little English-language scholarship on this subject has been done) or from conversations with Urdu-reading friends, I have probably missed. My sincere apologies.

Nice! Good overview and so many recommendations.

Please do add JC Bose’s Niruddesher Kahini (1896)/Palatak Tuphan (1921), Jagadananda Roy’s Shukra Bhraman (1879) and Devaki Nandan Khatri’s popular epic fantasy Chandrakanta (1888) if you could to the pre-independence list.

It is due to Niruddesher Kahini that the scientist JC Bose is widely considered to be the ‘father of Bengali science fiction’. It was also the first sci-fi story to employ the ‘butterfly effect’ in a story, something that is usually (and erroneously) attributed to Ray Bradbury. More here: https://factordaily.com/jc-bose-science-fiction-new-worlds-weekly/

Also, it would not be amiss to mention here that Begum Rokeya’s Sultana’s Dream came out a full decade before Herland, and also that Rokeya’s Ladyland is utopian in nature. More here: https://factordaily.com/begum-rokeya-hossain-sultanas-dream-matrubhoomi-feminist-science-fiction/

I look forward eagerly to Part 2!

Fantastic article, Mimi!

Adding in a couple of my Early South Asian Spec faves:

Kylas Chunder Dutt’s short story (in English) “A Journal of Forty-Eight Hours of the Year 1945” published in the Calcutta Literary Gazette in 1835. It’s about a future rebellion against the British Empire, which fails.A decade later in 1845, his cousin Shoshee Chunder Dutt (who would go on to have a successful literary career) published a more polished story on the same theme, also written in English: “The Republic of Orissa: Annals from the Pages of the Twentieth Century.” The rebellion is set in the 1920s this time, and is successful. Both stories are also fascinating because they were almost certainly too seditious to have been published before 1835 or after 1857.

@@.-@ Many thanks for you answers! The third one is certainly food for thought!

Thanks for this list, Mimi!

At least a few of the Ghanada stories have been translated into English. I wrote a review of a collection of them here: http://thegloballycurious.blogspot.in/2015/03/mosquito-and-other-stories-by-premendra.html.

Keep up the good work!

@7, 8, 11: Thanks, guys! *waves* Added with acknowledgement.

Very interesting article. In your opinion, among the translated works into English, which of them are the most interesting for a contemporary reader in USA or Europe?

Thank you for this list and history! I’m always happy when some kind person goes through all the trouble of compiling one of these lists.

There are a large number of short stories and serial novels written in Tamil and malayalam between 1950s and 1990s which catered to an audience who were looking for pleasures of science fiction and weird tales. Cosidered as low brow literature many of these works are not part of the literary scenes anymore. Yet they enthralled generations of readers. Still remember reading those dusty books where leika the dogs encountering aliens and coming back to kerala with a newfound intelligence ending in tragedy. or the stories where a sherlock like malayali going along with gagarin to space only to fight with aliens.

Annotation must include Ascharya Vrittant (A strange Tale) story published in Peeyush Pravah a Hindi magazine from Madhya Pradesh, written by Ambikadatt Vyas in 1884.

Nice article! I particularly like how you dissociated mythological writings from speculative fiction. Any reason you did not include stories from Champak and Chandamama (Vikram aur Betaal, for example), or, for that matter, Chacha Choudhary?

Thank you for this great article! I am a middle school librarian and many of my students are South Asian. Do you have any recommendations or resources for good books for this age? Graphic novels and comics are especially popular!

A very informative and interesting article. Here is another suggestion for inclusion in any future article on this topic: Krishan Chander’s young adult book in Urdu – “Ulta Darakht” (The Inverted Tree).

Some where I read Bener meye (বেনের মেয়ে ) by Haraprasad Shastri was first bengali speculative fiction which influence J C Bose to write his palatak tufan.